When we talk about video games like the Souls series, there is a line separating games with reasonable physical difficulty from games that are unfair, then there must also be a line between tactical and puzzle games with fair and unfair games in terms of intellectual difficulty . Based on that reasoning, today we’re going to discuss what “intellectual difficulty” is, what the differences are compared to physical difficulty, and what makes gameplay fair or unfair when it comes to tactical and puzzle games.

The prominent chess player Johannes Zukertort once said that “chess is the fight against error”. I believe this is also a good intuition to understand what tactical games are in general: it’s about recognizing your mistakes and those of your opponent and using them to your advantage. Similarly, puzzle games also have error recognition, but the emphasis is placed on the player’s own errors (usually there is not even an opponent) and the solution is obtained more directly by logical-mathematical deduction.

To give a good technical answer to what? reasonable difficulty means in tactical and puzzle games, this article will be divided into three topics:

- the distinction between “intellectual difficulty” and “physical difficulty”;

- the concept of “honesty” applied to video games with an emphasis on intellectual difficulties;

- some tips to make tactical or puzzle games fairer.

What is Intellectual Difficulty?

As we know at least since then Gay Ludens (1938), by Johan Huizinga, games (not just video games in general) can be analyzed in two ways: for what they represent and for the challenge they present. Some games have a larger representational focus (with more elaborate plots, for example), while others are more focused on challenge, which can be physical and/or intellectual.

The design of the challenge in a video game plays an interesting role in allowing the player to participate in events that are “outside the real world” and the laws of nature, but still comply with certain rules of the game. This component in video games usually brings them closer to sports that can be played with one player or with many players.

Video games that focus less on deep symbolic representation and more on an interactive challenge are cases where the most interesting is not the practice of hermeneutics (the interpretation of meanings) but in its materiality and presence. Challenging video games, as well as sports, offer players and spectators “opportunities to immerse themselves in the realm of presence,” as Hans Gumbrecht wrote in In honor of athletic beauty (2006).

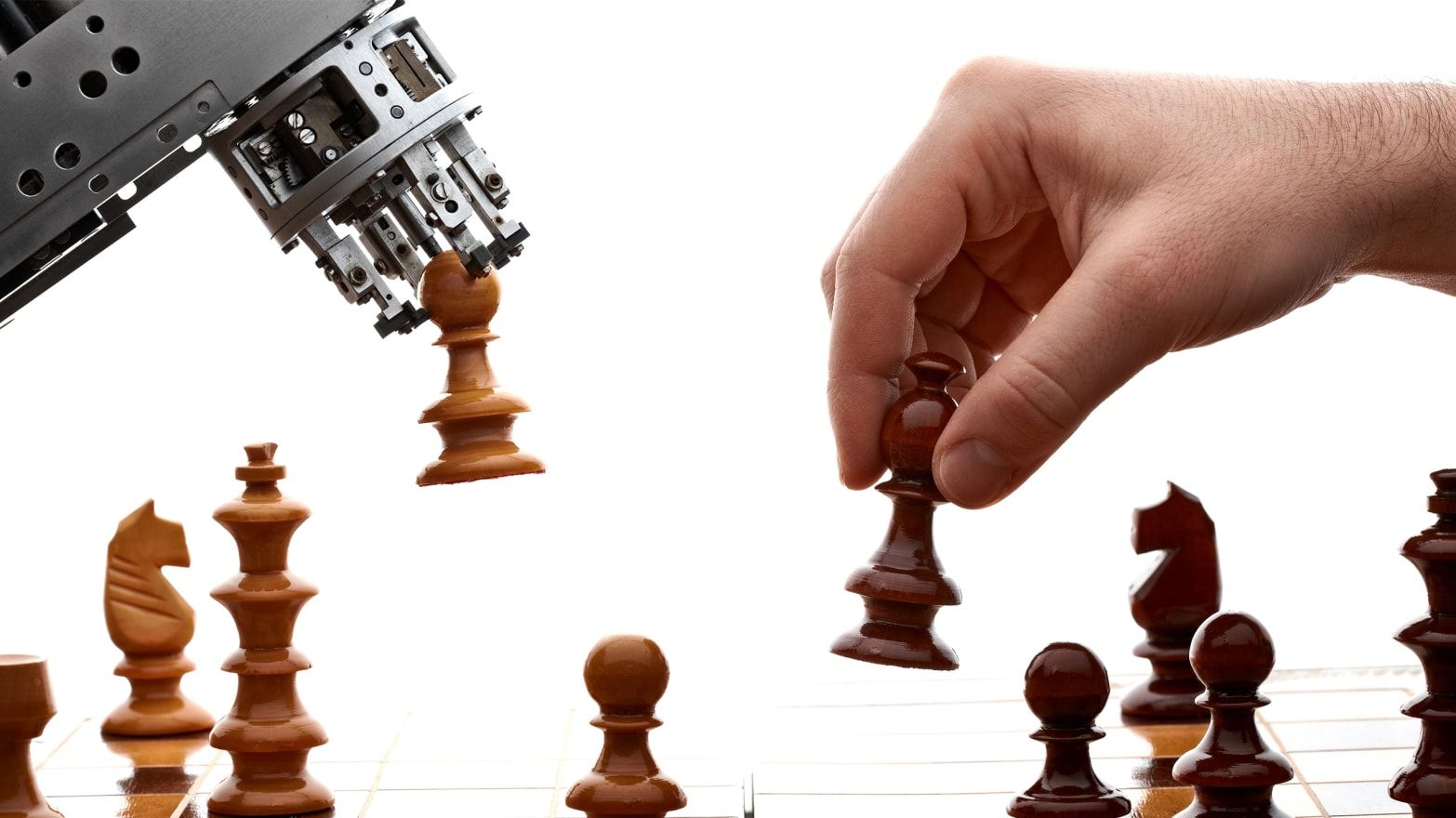

In video games, as in sports in general, this challenge can come in two forms: physical or intellectual. Boxing, for example, is a sport where the intellectual challenge is negligible; it’s all about physical challenge. Chess, on the other hand, is all about the intellectual challenge. Of course there is a degree, as in many sports there is a physical challenge, but also a considerable intellectual challenge. This is also the case with video games. A real-time strategy game, such as the Age of Empires series, also usually requires a significant physical challenge to take action quickly, while turn-based strategy games, such as the Advance Wars series, require no reaction time.

Similarly, a fighting game usually has a high degree of physical challenge (due to reaction time and hand-eye coordination), while a puzzle game usually presents a significant intellectual challenge because it requires, for example, to think more logically. It is worth noting that physical difficulty is not necessarily associated with enemies as a game can introduce physical challenges through platform gameplay, as Chris Priestman analyzes very well in his essay Tomb Raider: The World Behind the Walls (Heterotopias, 2017). This point becomes very clear when comparing the traditional classic Tomb Raider experience with its puzzle version: Tomb Raider GO (2015), directed by Jason Botta.

Here at SUPERJUMP, in Debating Difficulty in Video Games (2021), Josh Bycer discussed the difficulty theme but focused on physical issues. However, I would like to add a few words about how difficult a game is seen intellectually. And this has to do conceptually with the same two reasons Bycer mentioned:

- complexity of gameplay: the number of elements and functions assumed in the interactions;

- learning curve: learning design for the virtuous use of their systems.

If you want to dig deeper into the concept of “complexity” in game design, I wrote a specific article about it, The Difference Between Complexity and Depth in Video Games (2022). Here I will limit myself to emphasizing that puzzle and tactical games become more complex depending on the number of elements and relationships involved in the expected reasoning the player develops to obtain the solution of a problem or the victory of a battle. In this sense, it can be said that, objectively speaking, Go is more complex than chess, because there is more variation in the movement possibilities of units on the board.

In turn, the learning curve in puzzle and tactical strategy games becomes easier as scalability increases and level design becomes more progressive. So from a learning curve perspective, Triangle Strategy (2022) is a much easier tactical RPG than Tactics Ogre (2011), which introduces the player to several complex systems and subsystems at once.

What does “fair play” mean if it is a tactical or puzzle game?

In a recent SUPERJUMP article, What is Difficulty and Fairness in Video Games (2022), I developed two principles for honesty in video games, which were based on moral philosophy and on Huizinga’s premise about the nature of games presented in the previous topic. The principles of honesty are as follows:

- Transparency principle🙁i) all obstacles faced by competitors (real players or computers) must be recognizable to them; and (ii) all game rules must be available to participants.

- Parity Principle:🙁i) the game must offer equal conditions to participants of equal ability and equal numbers; and (ii) the game gives unequal legal conditions to competitors with disproportionate power or numerical disadvantage.

From these two principles we can immediately deduce that for most puzzle games these principles do not even apply, because they have no enemies or competitors. Video games like The Witness (2016), by Jonathan Blow, or Baba is You (2019), by Arvi Teikari, are neither fair nor unfair, they just have different levels of difficulty.

On the other hand, tactical games usually have different degrees of fairness in addition to different difficulty levels. Even if it is an offline tactical game, where the dispute is against a computer, a game should still be as fair as possible. This is no different than when a chess player is playing against a computer, it is unreasonable for the computer to start the game with, for example, more units than him.

We say that a tactical game is fair if it adheres to the principles of parity and transparency. I’ll give examples: In Fire Emblem: Three Houses (2019) – directed by Toshiyuki Kusakihara e Genki Yokota – before attacking an enemy you know the percentage of the chance of a hit. This ensures data transparency that your enemy also takes into account when choosing his plays. Hypothetically, omitting this information from the player would make the game more unfair and blind the player to a variable that only his opponent knows.

Now an example about parity. “Equality of terms” does not necessarily mean that competitors must have the same number of units. Unlike chess, in Go a player can start with fewer pieces than his opponent if he is a less experienced player. This also happens in tactical video games, when they offer difficulty levels, for example.

So a tactical game does not meet the parity requirement if it pits a novice player against a very powerful army. Game designers must always create the right conditions to make the game difficult by having an intelligent opponent, not just having an opponent with massive war power.

Note that through these examples, being fair or unfair in a game is not “absolute”, but it depends on degrees. A game can be fair in one aspect and unfair in another. For example, a tactical game might be transparent with some status, but omit others that are important. Moreover, these criteria of fairness are independent of those for difficulty: a tactical game can be difficult and unfair, difficult and fair, easy and unfair, or even easy and fair.

On the other hand, a puzzle game (usually assuming no opponents) is usually not unfair or fair, but only difficult or easy (to varying degrees).

Conclusion

If you make a puzzle game and it has no enemies, then you have one less problem (it will probably be a “fair game”), but you have to be very careful with the difficulty. The easiest way to deal with complexity and learning curve is to try to focus on one core mechanism and slowly tap into its potential. A Monster’s Expedition (2021) by Alan Hazelden and Patrick’s Parabox (2022) by Patrick Traynor are good recent examples of this that start with a very simple principle. Check out these games, they are really worth it.

On the other hand, if you are developing a tactical game, you should be especially aware of the “fairness” of your game. Be careful not to leave the algorithm that controls the opponent’s moves with game information that is not transparent to the player. To increase the difficulty, you should also always try to invest in the opponent’s intelligence instead of making him stupid and dependent on war power unless you have a good narrative reason for it. Into The Breach (2018) – by Justin Ma and Matthew Davis – is a relatively recent game that does very well in a minimalistic way and for varying degrees of difficulty.

Comments

Log in or become a SUPERJUMP member to join the conversation.

0 Comments