To describe We’re all going to the World’s Fair like a darker, depressing eighth grade feels like a disservice to what Jane Schoenbrun has created with their feature film debut: a film that explores the Internet’s appeal to alienated teens and adults. Yet comparisons are simple, and words fail to describe this atmospheric, experimental hidden gem.

Part coming-of-age story, part horror, We’re all going to the World’s Fair follows chronically online teen Casey (Anna Cobb), who, in an effort to cope with her loneliness, immerses herself in an online role-playing horror game called the World’s Fair. A newcomer to the internet frenzy, Casey watches videos of people transforming after playing the game – turning into plastic, gaining wings and the like – and begins to document the changes that happen to her.

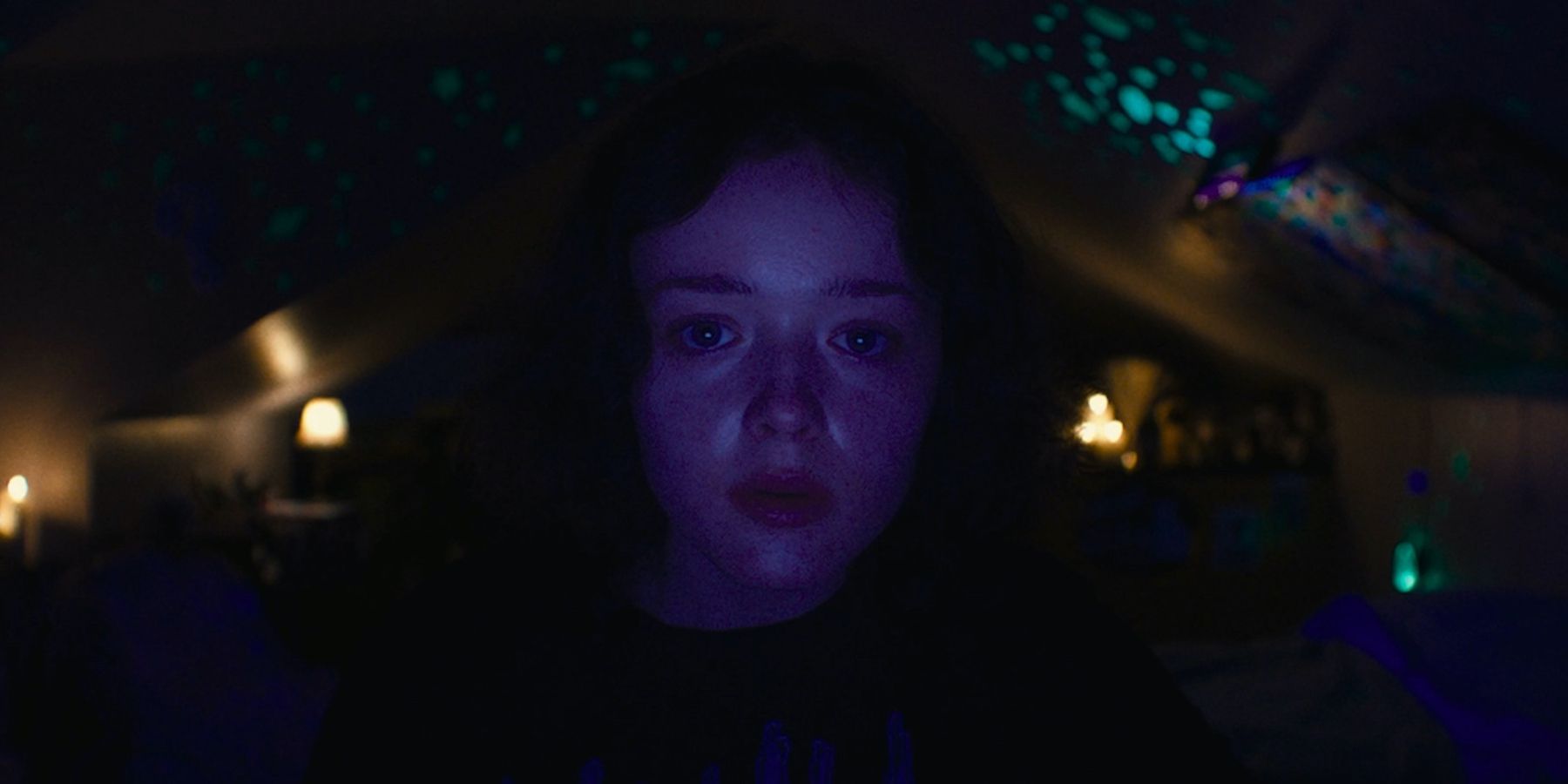

The movie opens with Casey alone in her messy attic bedroom, sitting in front of her laptop screen. “Hi guys, it’s Casey,” she tells the camera before trying again, “Hey guys, Casey here, today I’m taking on the World’s Fair challenge.” Moving to set the scene – making her bed and turning off the lights to reveal her glow-in-the-dark star stickers – she returns to her seat to repeat the words “I want to go to the World’s Fair” four times and prick her finger with a button pin. This act marks her initiation into the game and the beginning of her downfall.

Shortly after, a montage gives the viewer a glimpse into the kind of town Casey lives in: a nondescript, nowhere town with shuttered shops and empty parking lots. People live here, but the public doesn’t see them. Even Casey’s father can only be heard off-screen. With nothing to do and no one to be seen, Casey reaches for her laptop, offering her much-needed escapism.

She starts watching videos uploaded under the World’s Fair tag, and when she’s shocked, she doesn’t show it, lying motionless on her bed while 2D people share their mental breakdowns and turn into plastic. Casey is also starting to feel different, so she tells her camera on a tripod in the middle of the woods. “I know I should be cold right now, but I don’t feel anything,” she says — snow visible in the background. And since nothing out of the ordinary has happened so far, it’s hard to say whether this is a symptom of the World’s Fair or a metaphor for her state of mind.

We’re all going to the World’s Fair enters horror territory when Casey receives a video message from World’s Fair veteran JLB (Michael Rogers), showing her face distorted, along with the words “YOU ARE IN TROUBLE” and “I NEED TO TALK TO YOU.” Casey contacts JLB via Skype, and their relationship begins as it continues: with JLB “looking out” for Casey and Casey curious about who he is.

Their relationship is uneven, if not problematic. JLB has access to Casey in a way she doesn’t, because while she’s using her camera during their conversations – and viewers know he’s already watching her – JLB prefers to remain anonymous and instead uses a really creepy sketch as his profile picture from a real photo. There is also the risk that JLB is a predator as he is a middle-aged man talking to a teenage girl. However, the film never confirms or denies this, leaving it to the viewers’ interpretation.

One thing is certain: JLB is just as lonely as Casey. He too spends most of his time in his dark, cluttered bedroom, alone and watching other people’s videos. The difference is that he is older and logically wiser than Casey and can separate fiction from reality: something that Casey is increasingly struggling with. As her mental health deteriorates and she begins to experience the full effect of the World’s Fair, their relationship becomes fraught – and, by the way, the most interesting thing about the film.

Most people can be in an online relationship at some point in their lives. Whether they look back on them with horror or fondness (or a combination of both), they served a purpose and likely left an impact. We’re all going to the World’s Fair explores ambivalent online relationships, commenting on the internet in general.

Schoenbrun presents Casey and JLB’s relationship as both comforting and potentially dangerous, portraying the internet in a similar way. as they said Variety“It was important to me that [the movie] felt honest not only about what is scary, sad or dark about the internet, but also about what can be alluring and beautiful about the internet.” Schoenbrun – who is non-binary – has conflicting opinions about the internet itself, as they explain in the same interview that as a young queer kid, they used the internet as a lifeline and were drawn to the safety it offered: “safety of anonymity, and the safety of creating a self or experimenting with different versions of the self, detached from the physical form and of an identity I couldn’t control.” Likewise, they acknowledge the dangers of the Internet and even reveal their own (confusing) online relationship with an older man from the past.

We’re all going to the World’s Fair ends by thinking about the horror of ending these relationships and the unbearable uncertainty of knowing what happened to the other person involved. The upside is that the internet can only fill a void for so long before anyone moves on or goes crazy.

0 Comments