I’ve tried many of the mental health and wellness apps. First, there were Calm and Headspace, the obvious contenders. Then there was Fabulous, which is meant to help you build better habits, and then Thought Diary, which asks you to write down your thoughts and feelings at a set time each day.

During two quarantine weeks in January, I also became addicted to an app called W1D1, which sends you daily creative challenges (an important part of mental health for me). But all these apps are now all vacuuming amid a sea of apps that I eagerly downloaded and promptly forgot – probably because I had no real incentive to keep using them.

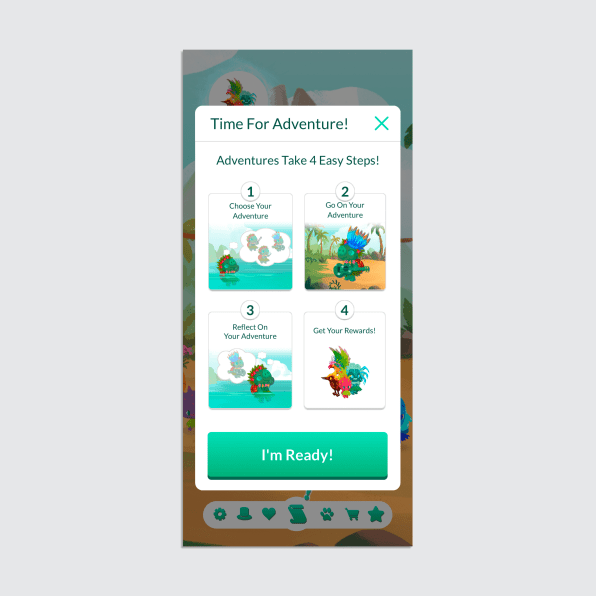

That’s why Craig Ferguson, a chief platform engineer in the Affective Computing group at MIT Media Lab, developed Paradise Island, a mental health mobile game that sends you on real-life missions in exchange for in-game rewards. The idea is to keep people coming back for rewards, keeping them more involved in the process.

Paradise Island is actually a sequel to The Guardians: Unite the Realms, which launched in 2020 and has nearly 13,000 users. Both games are based on a clinically proven type of therapy known as “behavioral activation,” which prompts people to get up and do things that are considered right for them. (Ferguson originally came up with the idea of helping struggling vegetarians who kept relapsing, but he eventually chose to turn his attention to helping those with anxiety and depression.)

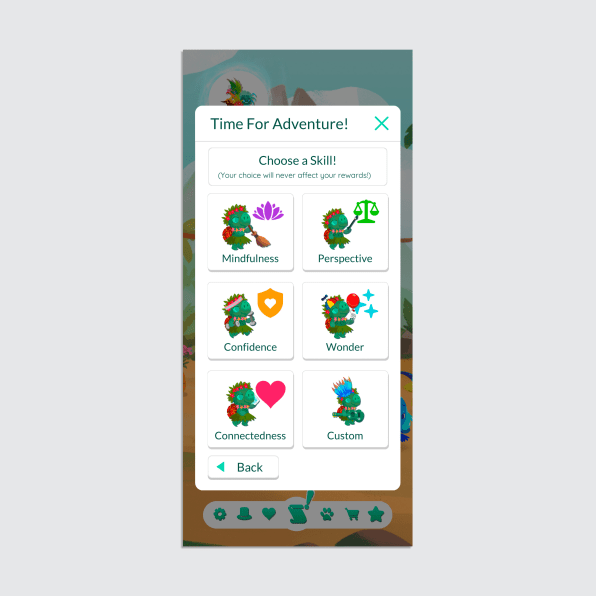

Players can choose from 75 activities, chosen with the help of a psychologist. These range from stretching for five minutes to painting the sky to texting a friend. (You can also do something of your own choosing.)

I wanted to check in with my distant friends more often, so the first activity I chose was texting a friend. After the app asked me how rewarding I expected the activity to be (“highly rewarding”), I reached out to my friend, leading to some much-needed, hour-long catching up the next day. Then I went back to the app, collected my “soul jewel,” a “golden ticket,” and three new “inspired pets,” and was again asked to think about how the activity made me feel after the fact (“incredibly worth the effort.” worth”).

Here I have to admit that I am not a big gamer. And while I don’t really care much about my daily golden ticket, I’ll be back for the gentle nudges the app provides, like a menu of activities that I know will make me feel better but probably wouldn’t otherwise join because, well. . . I didn’t feel like I had time.

Other apps I’ve tried insist that I check in at 6pm every day, or try to impose certain habits (like “don’t forget to drink water”) by giving me a nudge every morning. But Paradise Island puts no pressure on you and offers you a range of choices based on your mood and skills that day. I don’t know if I’ll last, but I’ve been using the game for about three days now and I’m curious what I’ll do next time I go back.

The game launched too recently to have any data available, but the original version had a 15-day retention rate of 10% and a 30-day retention rate of 6.6%, which may sound low but is actually more than 2. 5 times higher than that of the average mental health apps.

Of the 12,700 users who downloaded the first game, Ferguson says that 50% completed at least one real-life activity and 17% completed at least eight — a threshold often referred to in research papers as the minimum number of sessions. required to complete a behavior problem. activation course.

With Paradise Island, users get a brand new plot and setting, new pets to collect, a new mini-game and about 50 new real-life missions. The element of reflection before taking on the challenge is new, as is the ability to choose the level of effort required for your daily mission.

“Sometimes you wake up, your cat looks at you the wrong way, and you lie in bed all day,” Ferguson says. “We wanted people to be able to choose between little effort or a lot of effort.”

The game is designed to last approximately 21 days (it is limited to one real mission per day so as not to overwhelm people with depression). After that, the hope is that users have built up enough habit to stick with it.

“One of the goals behind the app is to teach people a lesson, to help them build skills and resilience,” says Ferguson. “If you do this enough, that reflection step is to make people realize, ‘When I was feeling bad, I really didn’t think running would help, but it did,’ and remember that.”

0 Comments