lIt’s been a tough year for shoppers looking for cars, electronics, and anything that requires a computer chip. Due to a global shortage of semiconductors, many companies are unable to fulfill orders or even finish products they have begun to assemble, warehouses are clogged and a lack of inventory across the country.

Buying a new PlayStation 5 console remains almost impossible. Several automakers have delayed production at their factories, delaying shipments of new vehicles. It’s even influenced more obscure products – just try to find an affordable dog wash booth these days. More than two years after the pandemic began to shake the global semiconductor supply chain, the companies that make the chips to power these products are still feeling the pain.

Washington’s solution

The Senate could offer some relief in the coming year as it votes this week on a $52 billion package that would provide financing and tax credits to companies that manufacture chips and invest in domestic manufacturing. If passed by the Senate as expected, the House will consider the legislation before the August recess, which starts in two weeks.

“We are too dependent on other countries for chips,” Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo told TIME on Tuesday, as the Senate voted to limit debate on the spending package. “Chips are the most essential item in modern industrial equipment, medical technology and every piece of military equipment.”

The burst in federal spending is designed to boost domestic chip production growth, according to supporters of the bill, but it could be years before consumers see the effects when shopping for new electronics.

For many of the largest tech and automotive companies, semiconductors used to be a relatively inexpensive part, one that cost just two cents to produce in the 1970s. Now these small electronic switches are the biggest obstacle to prevent more sales.

For example, an iPhone 13 needs about 60 semiconductors. The PlayStation 5 requires about 130. Javelin missile systems have about 200 chips and advanced defense helicopters have more than 2,000. For cars, the problem is even more extreme. The Porsche Taycan contains about 8,000 chips. And while the global microchip crisis may ease after two years, tech companies and automakers are striving to gain more control over their supply of chips and raw materials.

Read more: Intel Unveils Plans for Massive New Ohio Plant to Combat US Chip Shortage

The deeper problem

But with chips in the spotlight, many in the industry are warning lawmakers that a sudden surge in government funding won’t solve the lingering chip shortage.

“It’s not just a shortage of semiconductor chips. That’s the end product,” said Michael Hochberg, president of Luminous Computing, a California-based chip startup developing light-based semiconductors for artificial intelligence. “It is a shortage of semiconductor talent, a shortage of semiconductor equipment and also a shortage of capacity for semiconductor manufacturing. It’s all those things at once.”

Each chip has to be embedded in one of those ubiquitous green circuit boards to work, much like how a brain needs a body, says Travis Kelly, CEO of the Arizona-based Isola Group and president of the Printed Circuit Board Association of America. These printed circuit boards require laminate, copper foil and fiberglass yarn in addition to other scarce raw materials.

“In the past, semiconductor manufacturers could just assume they would get these parts from a FedEx catalog and not worry about them,” Hochberg says. “It was like breathing the air outside. Until about two years ago, they weren’t worried about parts availability.”

“Unless we tackle the whole microelectronics ecosystem, we’re not really securing our domestic supply chain,” Kelly says.

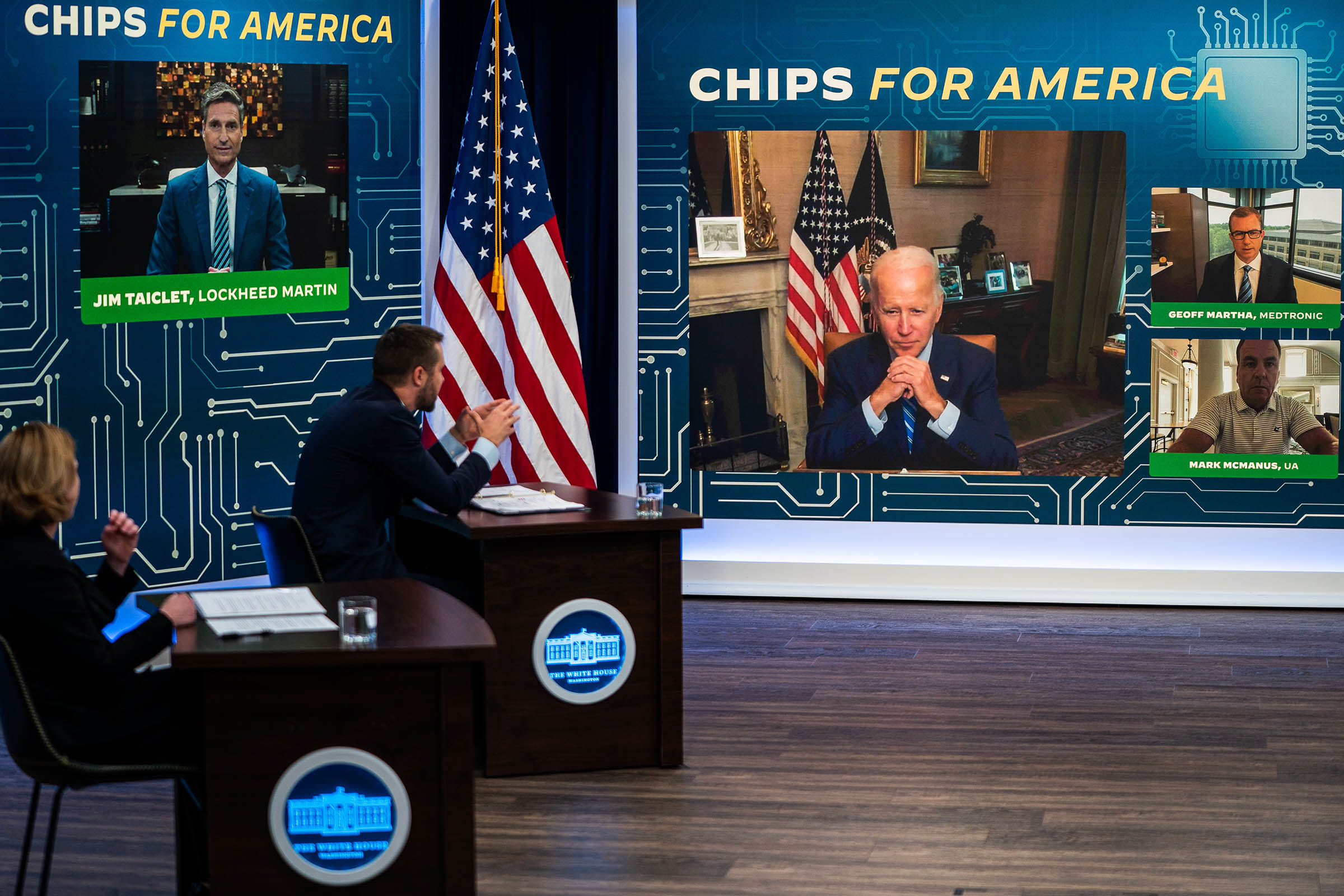

President Joe Biden discusses the importance of passing the Chips Act on July 25, 2022.

Demetrius Freeman—The Washington Post/Getty Images

National security concerns

Kelly’s printed circuit board manufacturer, Isola, is one of the last US companies to produce printed circuit board laminate in the US. country. “It’s a single point of failure,” Kelly says. “Think about that for defense.”

Lawmakers and those involved in the supply chain are now sounding alarms about the lack of American-made semiconductor materials. Two decades ago, the US produced more than 26% of the world’s printed circuit boards. That number has now fallen to 4% as more companies take advantage of the tax benefits and lower labor costs of working abroad. China and Taiwan, in particular, have become hotbeds for semiconductor and printed circuit board factories, with their governments investing heavily in chip manufacturing and building onshore resources for the chemicals and tools needed to support an independent industry.

“There is no more important strategic asset than semiconductors,” Hochberg says, listing examples ranging from national security to artificial intelligence. “If we want to maintain a technical and strategic advantage for AI, information warfare and military systems, when these chips are at the heart of these systems, it will be necessary to get ahead of this problem.”

National security concerns about semiconductor manufacturing abroad have been a key element in getting Congress to take action against the CHIPS bill, a senior legislative adviser to Raimondo told TIME.

“People may not care where the circuit board comes from when they operate a toaster, but they do care for war fighters and military applications,” says Isola’s Kelly.

Only a handful of advanced semiconductor factories, known as fabs, remain in the US today. Building new factories can cost between $10 and $20 billion and take up to five years to build, given the complex equipment and chemicals required to run a factory. And the process of actually converting all those materials into a final chip alone takes almost three months.

“It’s all silicon wafers, substrate, chemicals,” Raimondo says. “This stuff isn’t made in the United States, and it’s shocking.” Congress hopes that suppliers of all these parts will be encouraged to move to the US as soon as factories are built again domestically – a key objective of the CHIPS Act. “If TSMC builds a megafab in Arizona, or if Intel builds a megafab in Ohio, the entire ecosystem of talent and suppliers will evolve [there]”, explains Raimondo.

What’s next

Some executives are seeing the semiconductor shortage dwindle as vendors stock up on chips and other components. South Korean chipmaker TSMC, the world’s largest contract manufacturer, warned of “excessive inventory” in the semiconductor supply chain that will take the rest of the year and beyond to rebalance. Not all semiconductor foundries have had the same fortune, but it’s a positive sign for the technology and automotive industries that rely on these chips.

Korean automaker Hyundai recently posted its best quarterly profit in eight years, and Swiss engineering firm ABB, which relies on semiconductors to build industrial technology products, said it is finally seeing relief in its supply chain after years of challenges. “We are now in a situation where we have much better commitments from the suppliers,” ABB chief executive Bjorn Rosengren said in a July 21 earnings call.

And the White House and the Commerce Department are optimistic that companies will announce investments in the US chips industry if the funding of the CHIPS Act is signed into law.

“It’s not very different from what you see in Germany and Italy, which have allowed themselves to become overly dependent on Russian oil and gas,” Raimondo said. “That could be the United States if we don’t take action now.”

More must-read stories from TIME

0 Comments