Pasokon Retro (opens in new tab) is our regular look back at the early days of Japanese PC gaming, covering everything from specialty computers of the 80s to the happy days of Windows XP.

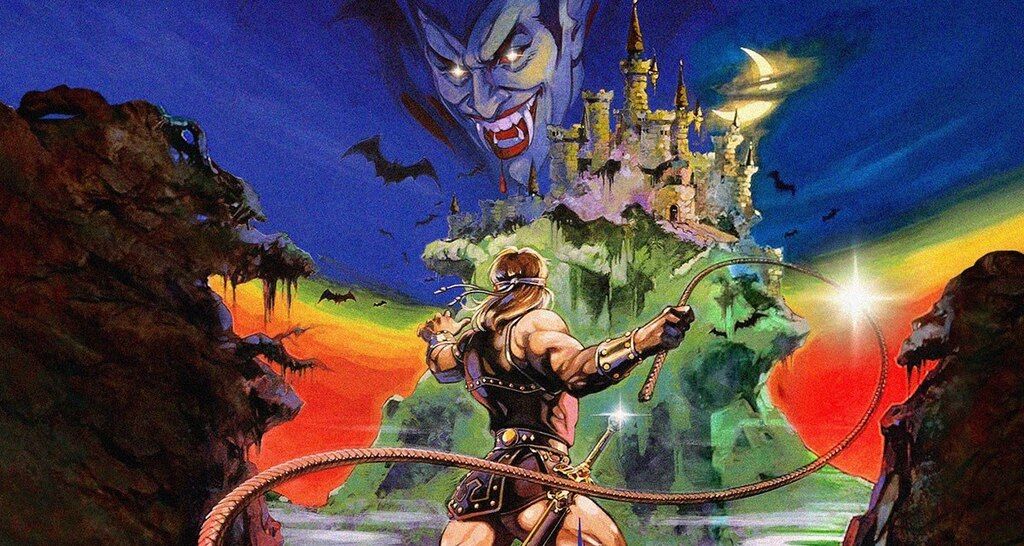

Everyone loves Castlevania. Everybody. Konami’s 1986 megahit is a Nintendo classic packed with iconic monsters, rousing Belmonts and rousing music. The gothic-inspired stages are streamlined to perfection, each linear portion of each stage a tightly designed challenge intended to test, but not traumatize, experienced gamers.

But what if they hadn’t been?

For once, this isn’t a wild hypothetical question, but something that anyone can play for themselves thanks to Vampire Killer, an exclusive game on the Japanese PC from 1985, the MSX2. Konami created Vampire Killer as an alternate version of the same Dracula-flavored concepts and released it at almost the same time as its more famous cousin.

There are many differences, but the biggest is this: progress isn’t just made by surviving one area and reaching the entrance to the next, like in most Castlevania games (and most platform games in general). Vampire Killer also requires its players to find the only special key hidden somewhere in the same area to unlock a door at the end of each stage as well. These special keys aren’t even out in the open, but often hidden behind breakable walls and blocks that are visually indistinguishable from others, unless Simon happened to be carrying a rare secret-revealing item in his inventory at the time.

To make this key hunt more manageable, each stage is a free-roaming area with no time limit, allowing players, at least in theory, to literally go back and forth all day in a single stage trying to find the damn thing. As if this wasn’t disorienting enough for anyone making their way through Wallachia, some specific sections of levels (and sometimes entire stages) wrap around themselves. You can start a level to the right, but walk to the left to explore parts of it “backwards” instead.

Later on, the game offers a few light puzzles based on this mind-boggling feature, including one seemingly designed to remind players that this screen-wrapping activity can be applied nonsensically. vertical and horizontally meaning that dropping from the bottom of the screen below could cause Simon, with perfectly executed 80s game logic, to get out of the top from the screen “above”.

(opens in new tab)

For all my complaining, in practice these key searches are not as confusing or obnoxious as they may sound. Knowing that something is hidden and I have to search and think through a world full of traps and monsters to find it is… quite exciting actually. I already know what to do even if I don’t quite know how I’m going to do it on a new level. The limited-use maps scattered across most levels offer even more help: a quick tap on F2 reveals not only an overview of the basic map of the entire level, but also Simon’s current location and even a large red arrow pointing the exit door marks.

Even in a game where death with a capital D is literally waiting around the corner and I can go through some stages backwards, I always know what to do and to some extent where I’m going.

Despite these fundamental changes to Castlevania, many areas still clearly mirror their Nintendo-branded counterparts. Frayed red curtains still hang by high windows as purple-colored zombies run across the same floor, mermen still jump out of the water below, and to my hair-pulling frustration, that bit with the floating medusas and the small platforms still rearing its ugly head. But all of these semi-familiar spots are made with a wider color palette than the NES could ever have dreamed of. The areas and features that don’t perfectly reflect the Castlevania we all know and love often introduce their own clever ideas, perhaps expanding a unique location that ended too early in the console game Stage 12 has a simple background feature – that big one. and strikingly Simon-sized sewer vents – effectively turning them into doors leading to new underground areas that don’t exist in any other version of the game.

Though living long enough to see that can be a brutal challenge: unless you bought a separately sold cheat device also made by KonamiVampire Killer only gives you three lives to lose – and no sequel.

This sometimes led me to want to stop playing not only Vampire Killer, but Castlevania as a whole, everything else Konami has ever made, and then throw the whole hobby in the sun for good measure. Fighting carefully through stage after stage to lightly brush one enemy once, and watching the kickback that Simon throws into a bottomless pit before dumping myself back at the title screen can do that with one person.

The thrill of exploration is dulled by the way all enemies respawn as soon as I leave the screen, inevitably resulting in me losing health to monsters I’m sure I’ve already defeated. It may have been a technical necessity, but it still stings. But while the game may be downright bad in some places, a little relief always seems to be just around the corner. Removing a wall sometimes reveals an old woman willing to sell powerful items or even complete cures for a reasonable number of hearts, or maybe there’s a treasure chest with the nearly groundbreaking usable hourglass item waiting just before the end of the level boss room, which could have been a tough fight, turns into a complete pushover.

These forced iterations in the earlier parts of the game create familiarity, which in turn puts the game’s challenges and apparent brutality in a different light. The second time around, I know I don’t have to waste my time going up a certain flight of stairs: if I hold on just a little longer, a complete cure is close at hand. I know not to hit that candle because it will drop a slime enemy, not an object. It’s really satisfying to get better, to see those old game-end problems turn into quick and deliberate moves that lead straight to the right area and then straight to the locked door – with maybe a brief distraction for a very specific treasure chest and the useful item inside.

(opens in new tab)

Even after a little practice, opening the “maze” of stairs and rooms that I can exit on either side has turned from a daunting sequence to something that is casually cleared up with minimal damage in seconds. That’s not bragging – that’s just Vampire Killer working as intended. This wasn’t designed to be something I make steady progress through and then put away forever, it was designed to be played over and over, my own knowledge and experiences are as much a part of Simon’s Dracula-destroying arsenal as any whip upgrade or item .

I do feel like I went through the wringer playing it, but I don’t mind it as much as I thought I would. Not even when Simon grazed a platform just above his head, the slight collision with the architecture changed his arc in the air just enough to send him crashing fatally to the depths below. If I’m being honest with myself, some of Castlevania’s more infamous segments really make it Lake make sense in this MSX2 version of the game, as their difficulty is offset or even negated by items that simply don’t exist in the NES version.

The NES Castlevania may have become firmly entrenched in our collective gaming consciousness forever (helped in no small part by the console’s massive popularity in the US and Japan and the continued nostalgia for it), but Vampire Killer remains an ambitious look into an alternative , more free form , horror platformer – a concept that Konami would return to several times over the years, until they finally found the masterpiece hiding in this go-anywhere gothic game: Symphony of the Night.

0 Comments