In 1980, nine-year-old Rawson asked Stovall for an Atari 2600 for Christmas. Santa didn’t play along.

“I didn’t get one, but our neighbors have one,” he says. After that, Stovall wouldn’t leave getting an Atari to chance. “I was like, I can’t trust Santa this year, I have to make it happen myself.” Stovall began picking pecans from three trees in the family’s backyard, peeling them, halves them, and package them for sale — eventually making about $220, enough to finally buy the console of his dreams. “My parents supported all of that, but my father thought video games were a waste of time and money,” he says.

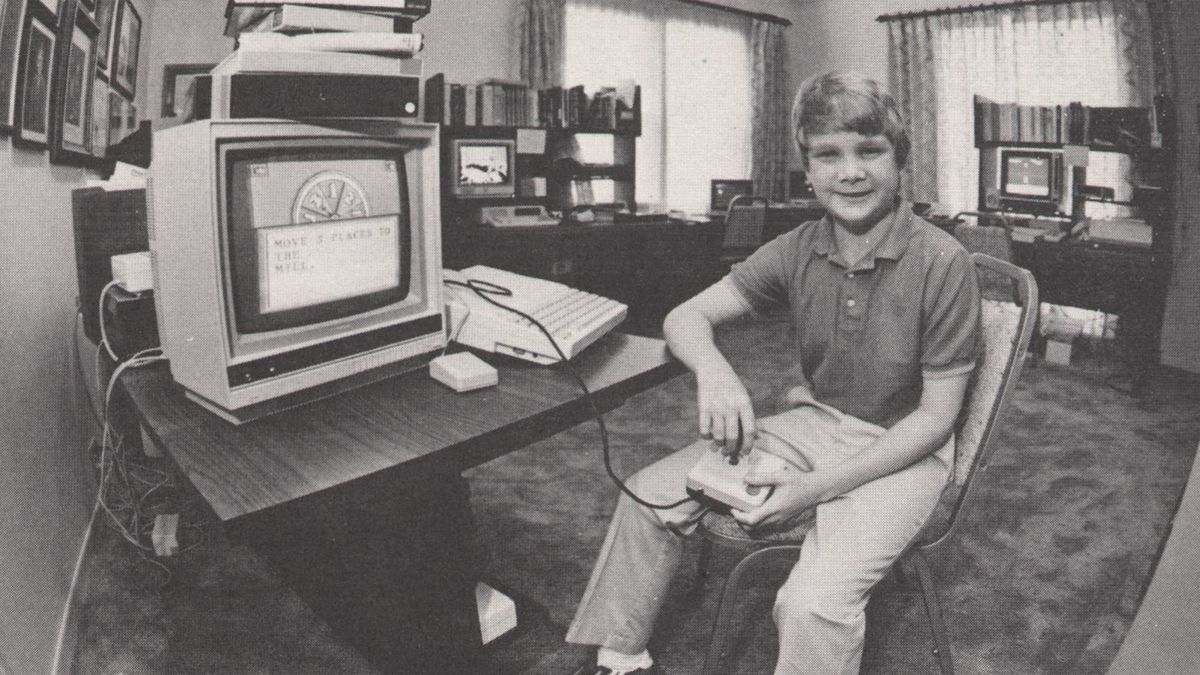

The Vid Kid would stop by newspaper offices in a three-piece suit with a briefcase

Not long after, Stovall became the first video game journalist to have a weekly syndicated column in the US.

“The Vid Kid” was born in the Abilene Reporter News – Stovall’s local Texas newspaper – a year after he bought his 2600 and realized that video games were also expensive (about $30-40 per cartridge in 1982 money, or $91- 122 today). “Games back then didn’t often have pictures of the game on the back,” he says. “All you really had to do was the packaging art, and the title, and maybe the reputation of the game company.” The lack of coverage spurred Stovall to advocate for game reviews as a necessity for a new generation of consumers.

“What struck me were TV show reviews. I’m like, they’re free, check them out!” he says. “Like it or not, you can decide! But there was nothing for video games.”

Stovall, who already had a lot of experience with cold calls and door-to-door visits for school fundraisers, turned to Dick Tarpley, then editor of the Abilene Reporter News, with six pre-written sample reviews. The newspaper decided to give him a writing test to make sure his parents weren’t doing the work for him. “Their entertainment editor took me to Tron, and then we both came back to the newsroom. And on computers, which was my first time — it was like a green screen and they had to teach me what word processing was — we wrote reviews,” says Stovall Both reviews appeared in the paper the next morning, and the rest, as they say, is history.

The Vid Kid started on a six-week trial basis. Stovall devised a report card style scoring system (opens in new tab) with well-known figures that his readers would understand. “It was a good gimmick, the guy who did the report for a change,” he says. Stovall’s father, a regional director of the Texas State Health Department, took him on work trips to several cities, where he would visit the newsagents in a three-piece suit with a briefcase. “I single-handedly put it in a dozen different newspapers, most of them in Texas,” he says. He expanded to the San Jose Mercury News and “about 25 newspapers” before the column was further syndicated by the Universal Press Syndicate. The suit and briefcase routine was an important part of his strategy – he believed that adults would hear a sharply dressed boy much sooner than another adult, and the familiar image of a suitable Stovall eventually became canon.

Stovall knew how to think big thanks to his school fundraising experiences. Instead of visiting the same old houses, he strategically went to offices, banks, and oil and gas companies, where he spoke to executives and sold lottery tickets en masse. He applied the same global approach to syndication targets for his column. When he first started writing, he had a fantasy of getting paid $50 per column. “All I had to do was publish it in 100 newspapers, and then I’d just write one article and go to Hawaii every month,” he says.

Instead, he was making $5 a column, which was still unsustainable for a kid who was maxing out every week. “But if you can send it to 10 newspapers, that’s suddenly about $50 a week, and that’s better than shelling pecans.”

The original streamer

Meet the original streamer (opens in new tab): At the age of 12, JJ Styles had his own publicly accessible game show in 1993.

In 1983, he needed special dispensation to attend the Chicago Summer Consumer Electronics Show as a minor, where he worked on the show floor with business cards and conducted interviews with Activision’s Nolan Bushnell and David Crane. At that time, he was already syndicated in 11 newspapers. A curious New York Times writer saw him and reported on him, which was a game-changer for the Vid Kid. By the mid-1980s, Stovall had appeared on The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson and CBS Morning News. In 1984, he gave the keynote speech at Bits & Bytes – the first national computer show for children – where Sierra showed Mickey’s Space Adventure and Mindscape demonstrated Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom.

In 1985, he even introduced the NES at Nintendo’s North American launch in New York. “I was there, but I didn’t recognize it as such a big moment in history at the time,” Stovall recalls. It was just after the Atari market collapsed and the general public sentiment was that video games were over. “At one point I had about an hour when Miyamoto showed me [Super Mario Brothers]and I just loved it when I first saw it,” he says. Stovall remembers being obsessed with Mario, but months later he didn’t get his own copy. When he finally got an NES, he had to get a piece of wood into the console to leave the game cartridge in. “I just thought it was so bad,” he laughs.

For someone who has been at the forefront of how games were written in the United States, Stovall remains humble about his influence. At the time, his approach to reviews — unsurprisingly given the overwhelming excitement about new technology at the time and the fact that he was a kid — was mostly celebratory.

“With the idea that any press is good press, I wanted to put good press on good games,” he says, citing two negative exceptions: Pac-Man for the Atari 2600, which he felt was such a big release. was that it had to be written about, and Rambo for the NES. “But I think almost all my reviews were positive, just because there were so many good games.” In between the fan mail sent to the paper, he also received “weird hate letters” from readers, showing that some things just don’t change.

When it came time for college in the late ’80s, it was game over for the Vid Kid. There were no game-related degrees at the time, so Stovall studied film. He then worked at EA, Sony, Activision and MGM Interactive, in various roles as a tester, QA manager and producer. Today, Stovall is a senior designer at Concrete Software, working on mobile games. “My perception is that games are harder to make than movies or TV shows,” he says, pointing out the unpredictability of changing software, outdated hardware, and “a million ways things can go wrong.” In his spare time, he slowly rummages through eight boxes of video game history from his mother’s house, filled with artifacts from his childhood career.

He’s thinking about writing another book about that chapter of his life (his first was an 80-reviewed game collection, The Vid Kid’s Book of Home Video Games). “I was watching Stranger Things with my son and I’m calculating how old those kids would be today, if it were all real,” he says. “And said, ‘Oh wait, the same time they did this, I was writing about video games’.”

0 Comments